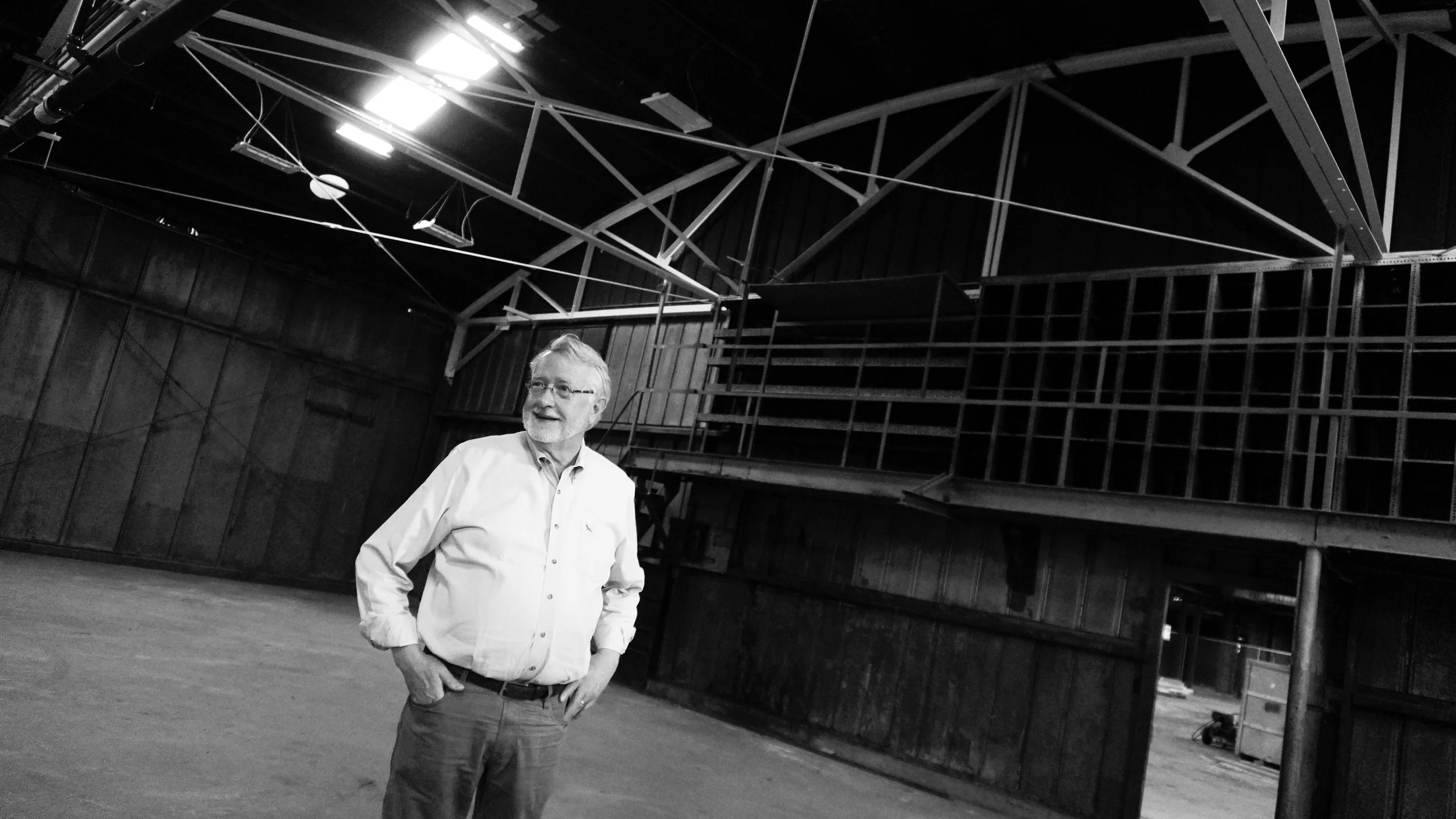

Jack Coleman

Rosedale, MS

Jack Coleman is a busy man. A native of Rosedale, MS, he returned to the town after four decades working as a lawyer in Washington, D.C. In his own office, he dresses in freshly-ironed formal attire that belies his buoyant and talkative character.

Dedicated to the prominent moonshiner Perry Martin, the Rosedale Distilling Company recently acquired the federal distilling, importing, and wholesaling permits necessary to move into its next phase of development, that of production. Once that commences, the company will be the largest distillery in the history of Mississippi.

Here in Rosedale, Martin’s name is legend––and Coleman, who once brushed shoulders with Martin as a child, has obtained the commercial rights to the Perry Martin name. Coleman, evidently, is a savvy businessman. He is also the mayor of Rosedale, a town of nearly 1,500, but he “wouldn’t consider [him]self a politician,” he said.

Prior to his return to Rosedale and subsequent election as mayor, Coleman served as a lawyer in the Army, before working for Ronald Reagan as an appointee for three and a half years. He then led the National Trade Association of Government Contractors before joining the Interior Department as an environmental lawyer, with a focus on cases relating to offshore oil and gas.

“There were a couple of multi-billion-dollar cases [for which] I was the lead lawyer,” Coleman recalled.

After that, he worked on Capitol Hill for another six years. After a lengthy tenure in D.C., along with an unsuccessful, albeit Reagan-endorsed, run for Congress, Coleman moved into private practice. “I plotted my escape from Washington,” he joked. “...But it was not escaping from Washington [so much as] escaping back to home.”

“I wanted to come home and do something fun and exciting and something that is beneficial to this community and…the Delta,” Coleman explained. “…something that would boost the tourism business [and] be profitable.”

With a jovial sense of gravity: “And, three, it had to be something that helped us tell…and preserve the history of this area, and particularly my hometown of Rosedale.”

Growing up in Rosedale, Coleman enjoyed an idyllic childhood. He played an array of team sports: football, track, basketball, Little League baseball. Living along the Mississippi River, he “could ride [his] bicycle anywhere.” There were lakes for fishing and fields for duck-hunting.

“It was simple and easy and really wonderful, frankly,” Coleman said.

By the time Coleman was eight years of age, in 1961, he was working for his grandfather’s hardware store and lumber company. His grandfather’s only grandson, Coleman was paid between $0.20 and $0.25 an hour.

“At that time, it was so inexpensive to entertain yourself in this community,” Coleman reminisced. It cost $0.15 to see a movie at the nearby theatre and a nickel for a bag of popcorn or a Coke. Somedays, in fact, he earned enough to get hamburgers at Michael’s Café before the movie started. “…even if your parents were off doing something else,…the lady who owned the picture show would take you home.”

Back at work, one of Coleman’s grandfather’s regular customers was “none other than Perry Martin.” Martin purchased barrels for his liquor and copper for his stills, among other hardware equipment, directly from Coleman’s grandfather. This is a story that Coleman relishes in telling––the glint in his eye as he recalls it speaks to a genuine adoration for, if not obsession with, the history that Perry Martin inhabited.

Coleman didn’t know it then, but Martin was one of the most renowned moonshiners around, particularly in the Mississippi Delta. He “prided himself on his aged whiskey,” which was unlike the moonshine (i.e., unaged whiskey) produced by others.

In the 1920s, Martin, who had originally produced his whiskey on Big Island in Arkansas, moved across the river to Rosedale, MS. He then worked on publicly owned land, where “nobody bothered him because they wanted him to make his alcohol out there,” according to Coleman. This took place during Prohibition, not to mention in Mississippi––the first state to have statewide Prohibition, although this did little to hinder drinking habits in the region.

At the same time, Martin was a primary supplier to the Al Capone organization in Chicago. While it now takes 6.5 hours to travel by modern highway from Rosedale to Chicago, distance was a non-issue then thanks to the Illinois Central Railroad, which ran from Rosedale Street North all the way up to Chicago. It helped that Rosedale was a fishing town, and that there stood a large icehouse by the railroad: Perry Martin’s whiskey could then be packed beneath layers of ice and fish before being transported to Chicago.

The sheriff of Bolivar County, Coleman told us, had never met Perry Martin. Yet, “every New Year’s Day, he had a great big jug of Perry Martin whiskey at his front door,” Coleman said, with a note of glee.

When it comes to Rosedale, Coleman is chock-full of anecdotes. According to the 1920 federal census, he exclaimed, Rosedale was the most populous town in the most populous county in the state of Mississippi––“believe it or not.”

Coleman then discussed, at length, the competition between European powers for control over North America; a major settlement was just 20 miles from Rosedale, he said, “at a place called the Arkansas Post that was founded in 1686, before Natchez and before New Orleans.”

In more recent history, Coleman said, Robert Johnson lived with his wife in Rosedale in 1930. He was 19; she was 15, and seven months pregnant. When both his wife and the baby died, the family blamed him for “playing the devil’s music.” This, in turn, precipitated the mythology of Johnson making a deal with the Devil at the crossroads.

“If you have a good history, you learn it and you share,” Coleman stated. “If you don't have a good history, I’d bury it.” But with history like this, that he is ostensibly “excited and proud of,” said Coleman, “let’s uplift everybody with it.”

It goes without saying that Coleman cares deeply about Rosedale. Now, he hopes to “polish [the community] up” through launching his distillery company and employing grants from the state of Mississippi for “improv[ing] public infrastructure to support new businesses” like his own.

Thanks to his experience working as general counsel with the Natural Resources Committee in the U.S. House of Representatives, Coleman is familiar with “policies that incentivize development in certain areas” through the provision of tax credits.

“I knew about a lot of things that could be done that maybe a lot of folks around here didn’t,” he said. “I don’t want to just use that knowledge for our own company, but for our whole community…even more broadly.”

In Rosedale, Coleman has taken full advantage of historic tax credits to preserve historic buildings while simultaneously bolstering some of his new businesses in the area. “I would say 45% of our capital stack…came from selling our tax credits,” Coleman said.

While detractors would argue that Coleman is exploiting federal funds for his own benefit, proponents would point out that the businesses will, in what Coleman described as a “conservative projection,” create at least 57 new full-time jobs in the town.

Compared to Cleveland, Coleman argued, Rosedale has “more potential…for growth, for prosperity or the creation of jobs in multiple ways.” The port of Rosedale, which employs about 600 people, could “easily [employ] 2000 people,” he claimed, while cruise boats come four times a week to Terrene Landing, which provides tourists with direct access to the town.

“I had not really planned to run for mayor, but [I] realized last year that…I felt I was called to do it,” Coleman said. “…One of the reasons I ran for mayor is you can’t drive if you’re not in the driver’s seat.”

A white man, Coleman was an unlikely candidate for the mayoral race in Rosedale, a community that is 85% Black. “I’m not Black,” Coleman noted. “And so the conventional wisdom would tell you, I can’t win this election here.” He paused. “I won a four-way race with almost 60% of the vote.”

He described going “door-to-door”––“didn't matter what section of town I was in”––and speaking to residents of Rosedale, learning about their concerns and canvassing for his role. Their complaints, he observed, were “usually something local, close to their house,” relating to clogged storm drains, junk cars, and the undesirable presence of “substandard” rental properties.

“I always believed that I could win,” Coleman said. “I think I’d get 70 or 75% [of the vote] today. I think we’ve had a good five months. Not as good as I want it to be, but we’re just getting started.”

Some of the major issues that hound Rosedale and the Delta at large, according to Coleman, involve healthcare, police and fire response services, and education. Public infrastructure, too, is important––especially to Coleman, who is both mayor and businessman. He recently acquired a $640,000 grant to install “ beautiful historic looking street lights” on Main Street, “all the way down the highway from highway to downtown.” Now, he is looking to obtain a $750,000 grant to replace defective water lines in Rosedale.

Opportunities, too, are at a deficit in Rosedale, and Coleman is determined to change that. “I can tell you the saddest day in the life of most people who are from Rosedale was when…they had to leave here to advance,” he said.

Coleman intends on running for a second term as mayor. “The whole thing on economic…and community development is to get the ball rolling,” he said. “...And the biggest contribution that I could do, other than this [distillery], is be mayor and try to help move things along.”

Despite his many commitments, nonetheless, Coleman is happy. He is mayor of Rosedale; his businesses are going well. His youngest daughter and her husband, both of whom attended high school together in Arlington, VA, recently moved to Rosedale to be with Coleman. The husband, an alumnus of Ole Miss, will be the Chief Operating Officer for the distillery. With them, the young couple also brought Coleman’s grandson, Little Jack.

“Everybody wants a canvas to paint on,” he said. “You can make your mark on multiple canvases as you go through your life, professional canvases and then the joyful canvases, you know.” Now, he is in the “joyful canvas stage” of his life.

Said Coleman: “Every day here is a happy day.”