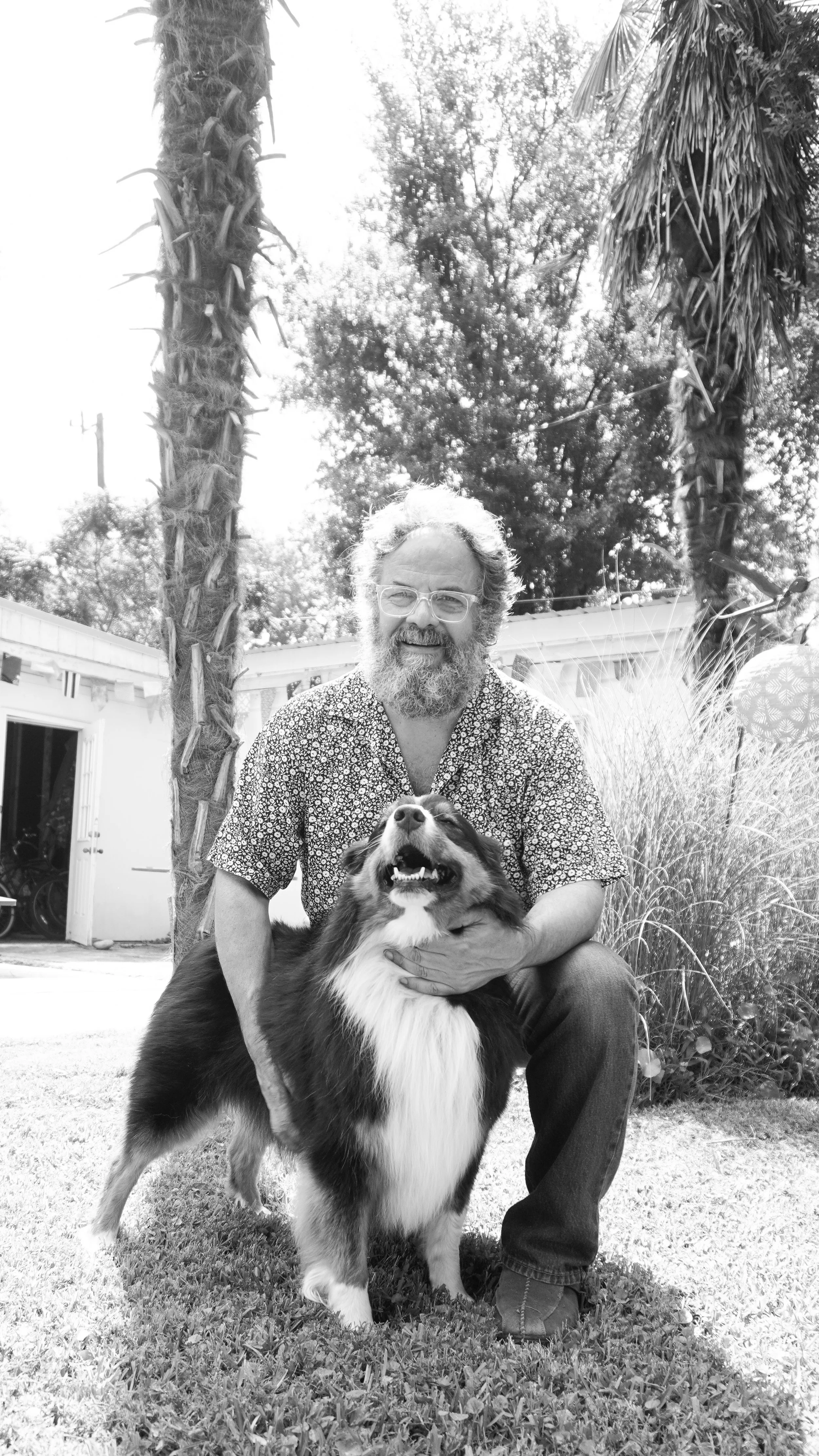

Scott Barretta

Greenwood, MS

A native of Charlottesville, VA, Barretta fell in love with the blues early on. As a teenager, he attended free events at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival, and later snuck into nightclubs in nearby Washington D.C. for the live music––rock, bluegrass, and the blues. “They didn’t really check I.D.s,” he said.

At college, Barretta studied sociology, with a particular interest in historical comparative studies of political issues. He ultimately completed a dissertation on homelessness during the Great Depression. Barretta then visited and intermittently lived in Europe, New Orleans, Mexico, and Guatemala before returning to Charlottesville for graduate school. Two years later, Barretta decided to pursue his doctoral degree at Lund University, where the focus of his studies took a sudden turn.

“When I got to Sweden, I had to switch my topic,” he explained, “because they don’t have homelessness, for one.” He opted to study music instead.

Meanwhile, Barretta wrote for the Jefferson Blues Magazine, a Swedish publication named after American musician Blind Lemon Jefferson. When the editor abruptly resigned, Barretta “ended up getting the keys to the office and becoming the editor [of Jefferson].”

At the same time, Barretta had approached various American blues magazines for his written work, primarily focusing on the development of an outside audience for the blues, including the middle class white people interested in traditionally working class Black music.

In 1999, Barretta was recruited by David Nelson, the editor of Living Blues magazine, to join him on the team as an editor. Originally founded in Chicago in 1970, Living Blues is America’s oldest blues periodical; it is now owned and funded by the Center for the Study of Southern Culture at the University of Mississippi. So, after several years abroad, Barretta found himself in Mississippi, the birthplace of the blues. Since 2002, he has taught sociology and anthropology at Ole Miss in Oxford, MS.

In Barretta’s view, the “broader context of his work” was the “cultural tourism wave” in Mississippi in the 2000s. In 2001, Morgan Freeman co-founded the juke joint Ground Zero in Clarksdale, MS, drawing national media and attention. Congress declared 2003 the Year of the Blues. That same year, Living Blues received funding to produce a magazine issue about blues in Mississippi, and Barretta began work on exhibits to be displayed in the B.B. King Museum, which eventually opened in 2008.

The Mississippi Blues Trail soon followed, providing, in Barretta’s words, a “physical infrastructure of sorts” to crucial landmarks in Mississippi through the continued establishment of historical trail markers. Barretta, along with Jim O'Neal, a former Living Blues editor, co-researched and -wrote the text for the markers.

Unlike other places, the history of the blues, with its endlessly mobile characters, necessitates “a different kind of tourism altogether,” involving long drives, stops at gas stations, and an understanding of the liminality central to blues and sharecropping history.

Funding for the Blues Trail primarily comes from the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Mississippi Department of Transportation. The first few trail markers came as prototypes in Indianola, near the B.B. King Museum; now, they are ubiquitous in other counties across Mississippi, including Sunflower, Washington, and Bolivar. As of July 2025, there are 220 trail markers and counting.

Barretta was also involved in the establishment of the Grammy Museum in Cleveland, MS, which was financed entirely by the state of Mississippi. The Grammys itself did not provide funding for the endeavor. Said Barretta: “It’s kind of like a franchise of sorts, right? McDonald’s doesn’t pay you to start a McDonald’s.”

As an instructor of sociology and anthropology at the University of Mississippi, Barretta’s responsibilities lie not only in researching the blues but also in teaching them––to students who are generations removed from the time period in which they originated.

“I try to keep up with who the current pop stars are, like Olivia Rodrigo,” said Barretta. “…it’s not music I would be listening to otherwise, but if I’m teaching 18 and 20 year olds [it feels necessary].” As an example, he pointed to the relational link between the blues women of the 1920s “singing about being abused by their men or wanting to have sexual freedom” and Beyoncé, with her songs about empowerment.

In discussing prominent songs from the civil rights movement, Barretta cited A Change is Gonna Come and Say It Loud – I’m Black and I’m Proud as examples. However, he also suggested that some less overt––and perhaps even more popular––titles were just as political. References to exploitation or mistreatment, for instance, were “often couched in terms of interpersonal relationships.”

“In the South, singing about how bad the plantation owner was not something you were going to do explicitly, right?” Barretta said. “And probably white owned companies that were going to distribute records in the South didn’t want to have a Kendrick Lamar on their label.”

Barretta harbours no illusions over the complicated legacy of the blues in Mississippi, a history that has been variously exploited within and without the community. “I think a lot of the problem, at least here, is who’s making the money?” he said. “I’d say it’s [white blues fans who own] the hotels, gas stations, the restaurants, and the clubs to a certain degree.”

From his perspective, the goal is not to exclude the current main audience of “older white guys,” but to make the blues more “appealing or accessible to African-American audiences,” who are otherwise turned off by what is commonly viewed as an exclusively “white space.”

Barretta took issue with people who seek to decouple race from the blues. Speaking of tourists wearing popular T-shirts emblazoned with the text “No Black, No White, Just the Blues,” he said: “It’s a nice idea, but the reality of it is no, people do think about race. You can’t ignore race…as a social factor.”

Asked for how he would define the blues after a career spent teaching and researching the subject, Barretta paused. “A blues artist might say, well, the blues is when you wake up and there’s no indentation in the pillow next to you,” he said. Alternately: “the blues is the experience of being Black in the United States.” Or, more simply, it is “melancholy.” Just like its history, the blues elude easy explanations––they refuse consignment to any singular definition.

“The blues has this possibility of transcendence,” Beretta concluded. “...at its essence, playing the blues is a way of getting rid of the blues.”

Barretta keeps busy. In addition to teaching and working on state-wide initiatives, he is a former columnist at the Clarion Ledger, has contributed to Mississippi Today, and co-hosted the blues radio show Highway 61 for over a decade.

At home in Greenwood, Barretta and his wife care for two Australian shepherds, two kittens, and several cats that linger in the front yard. The house, a warm, open-plan space, is festooned with an array of eclectic items––some relating to the blues, others best described as miscellaneous. A vintage jukebox sits at one end of the living room. All of it speaks to a life that has been built, perhaps inadvertently but never indeliberately, doing precisely what he loves.

“I’ve kind of learned not to plan things because you just never know what’s going to happen,” Barretta said. Quoting John Lennon, he stressed: “Life is what happens when you’re planning other things.”