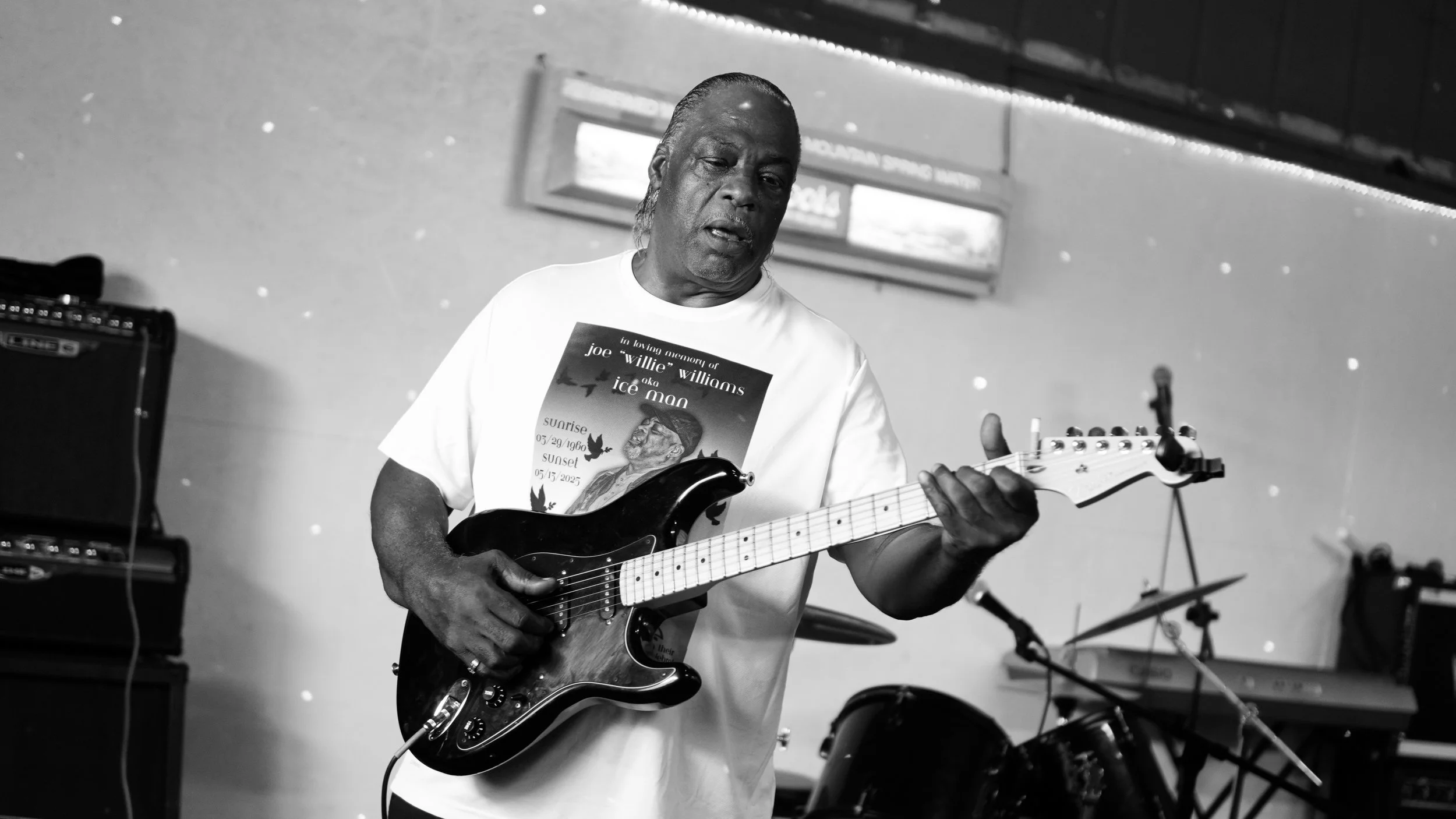

Terry “Big T” Williams

Clarksdale, MS

Terry “Big T” Williams is a blues legend. The godson of Big Jack Johnson, Williams knows that there’s more to playing the blues right––according to Big T, it’s about “liv[ing] it right.”

Big T was born in Farrell, MS, a small town on the outskirts of Clarksdale in proximity to the fields of Stovall Plantation, where the great bluesman Muddy Waters was reared. Big T’s father, a WWII veteran, was a sharecropper, and Big T himself was just one of 21 children. As a child, in Big T’s words, he was a “juvenile,” constantly “running into everything head-first.”

“Run into enough brick walls,” Big T noted, “[and you] get a headache.” He dropped out of high school in the 12th grade; he obtained his GED years later, when he found himself in the Mississippi Department of Corrections.

“As a kid, growing up in Clarksdale, all we had was winos and alcoholics and junkies,” Big T said. But there was one other thing: the blues.

In his youth, Big T had the privilege of encountering––and learning from––the likes of Big Jack Johnson, Johnnie Billington, Frank Frost, and Sam Carr. They were, in Big T’s words, “the most powerful blues players back in that time,” although he added that they were “discredited,” and “never got what they were due.”

“Big Jack was the most powerful blues player I ever seen and had the pleasure of being taught by,” Big T said. “[He] gave me the ability to be strong, powerful in my craft, because he was strong and powerful.”

Likewise, Frank Frost and Sam Carr of the Jelly Roll Kings were “ahead of their own time.” Big T also met Robert Lockwood Jr., who learned to play under Robert Johnson’s tutelage. “If you had a curtain and you didn’t see [Lockwood], you would swear that was Robert Johnson,” said Big T.

Hoping to follow in the footsteps of these “old greats,” Big T sought out their wisdom and support. Instead, they told him to wait his turn, and, in the meantime, had him practice by performing for years without pay.

“You got to pay for your education,” Big Jack Johnson told him. This was the requisite “down payment” for Big T’s career in the blues. It was, after all, only the beginning.

Growing up, Big T was best friends with Howard Stovall, of the very Stovall family that owns the historical land and property relating to Muddy Waters’ time on the plantation. At one point, Stovall began attending Johnnie Billington’s Delta Blues Education Program, from which Big T had already graduated.

“Johnnie used to tell him all the time on the keyboard, ‘Howard, you gotta chop it, chop it’,” Big T said, imitating his former instructor’s intensity. He then “walked over to the keyboard” and he showed Howard what it meant to be “choppin’ it.”

Billington was Big T’s first teacher of the blues, and he was a man of high standards. For five years, they practiced the same Magic Slim song together. According to Big T, Billington’s LP record of the song was uniquely scratched; whenever it played on Billington’s old hi-fi record player, then, the song would “skip” at a specific point. But Billington was resolute: they “had to play it just like the record.” “If it’s a skip, then we got to skip,” Big T shrugged.

Years later, listening to the song on the WROX blues radio station, Big T heard the song, polished and sans skip, for the first time.

“I swore up and down,” he recalled, “I said, ‘That’s wrong, that’s wrong right there.’” He went to Billington, who simply replied: “Now you can play it the right way.”

By 1991, Big T, Stovall, and Billington had founded the Stone Gas Band together. As a Stovall, Howard “had access to not just money, but power, to move the band further than me,” explained Big T. They did well, and the performances kept coming. “…a lot of us got tired.” As his career progressed, Big T became a “traveling bluesman,” spending a decade in Chicago and another decade in Memphis. Back then, he said, “Wherever I laid my hat was my home.”

Eventually, Big T landed himself into trouble. He subsequently spent six years in the Department of Corrections. “This is where my blues really started,” he admitted.

Upon leaving prison, Big T was introduced to Morgan Freeman, who later co-founded the Ground Zero Blues Club with the businessman and former mayor of Clarksdale, Bill Luckett. “[Freeman] cried on me at the drop of a hat,” said Big T, reveling in the memory. Asked how he did it, Freeman replied: “[I] just put myself in a sad position…and the tears come.”

Freeman and Luckett wanted Big T to play for their house band at Ground Zero, in Clarksdale. Big T agreed. Ground Zero Blues Club opened in 2001, and has been wildly successful in the years since.

“I’ve always felt at home when I’m here [in Clarksdale],” Big T said.

Some things have changed: Fourth Street, for instance, is now Martin Luther King Street, a decision that baffles Big T. “When I was a kid, man, Fourth Street was…everything,” he said. “You had musicians that was born here, Sam Cook, Ike Turner, these cats…Fourth Street was where all the partyin’ went on.”

Other things have not changed at all. “A lot of people come to Clarksdale and say ‘oh, Blacks and whites are getting along’,” Big T stated. This, he argued, was a gross misconception.

“It’s still there!” he exclaimed. “But it’s under the rug. Pull the rug back and you’ll see it.”

Around ten years ago, Big T and a friend were invited over to a bed and breakfast hotel on Park Street for a meal. Knowing Clarksdale, he warned the friend that it “wasn’t a good spot,” but his friend, a native of Indiana, promised that “that don’t exist no more.” Resigned, Big T headed over for breakfast, only for the waitress to refuse him breakfast. “No food,” he repeated. They were told they could have breakfast, yes, but they were to leave with it immediately.

When it comes to the blues, exploitative and discriminatory practices are nothing new. In the sixties, Big T said, “Elvis was the hottest thing we knew, and all he was doing was cover tunes: tunes that had already been done by Little Walter, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, and all these cats.”

The doors that were open for white artists, who alone capitalised on traditionally Black music, were not open for blues legends like Muddy Waters. By the time the doors opened for Black artists, Big T said, “[there] wasn’t nothing exciting about it, because it’d already been done.”

But Big T has devoted his life to the blues. He has walked in the footsteps of the greats, Muddy Waters and Big Jack Johnson among them, rubbed shoulders with the greatest bluesmen of the past and the present, and joined their cohort as a Mississippi icon in his own right. With his eponymous School of Blues, Big T now seeks to foster the next generation of blues musicians.

His hope, Big T said, is to “pass that tradition along to the youth under me, and make sure that they can carry it on and play it right.” He paused briefly.

“Or live it right.”