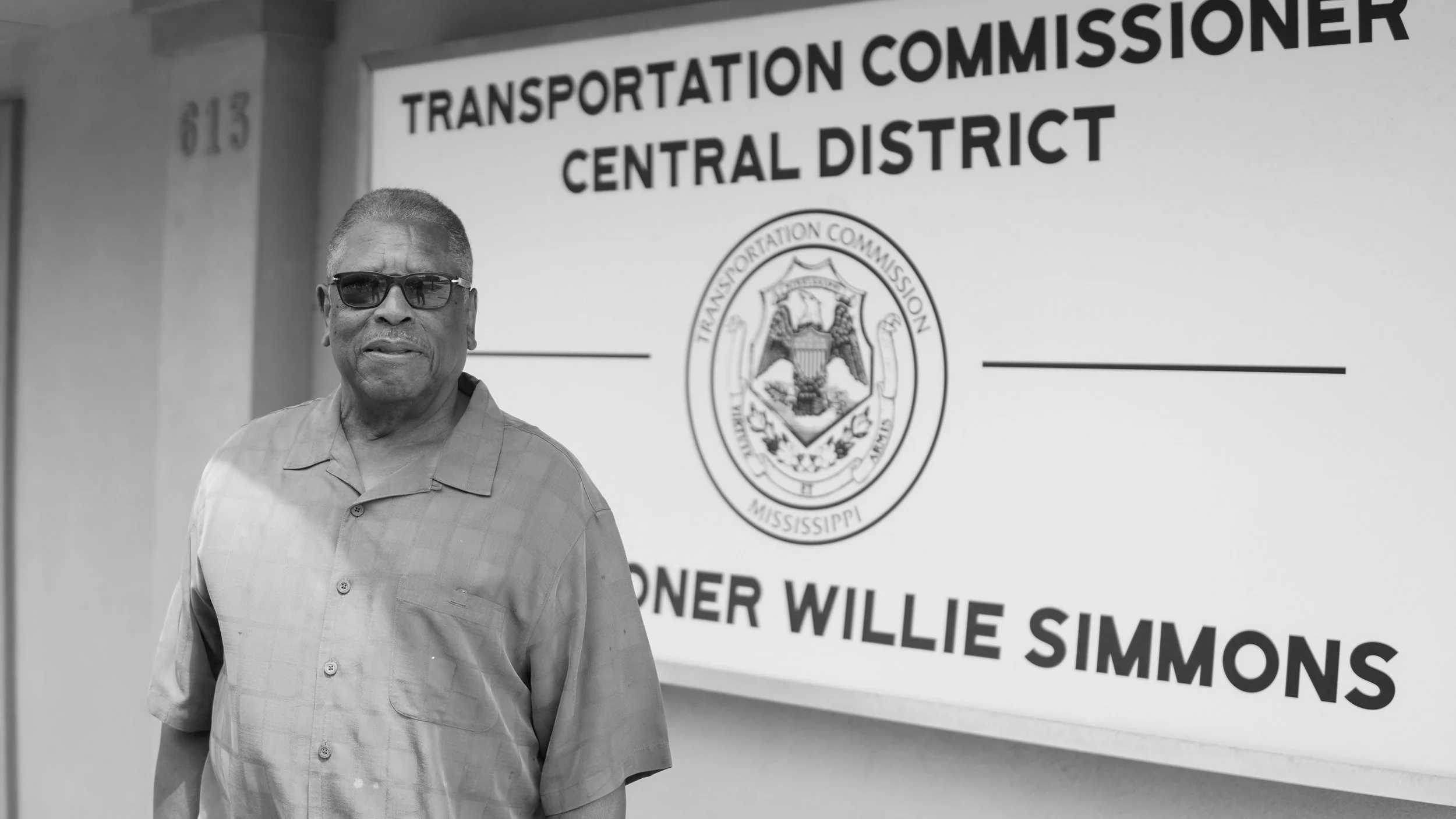

Willie Simmons

Cleveland, MS

Commissioner Willie Simmons likes to get things done.

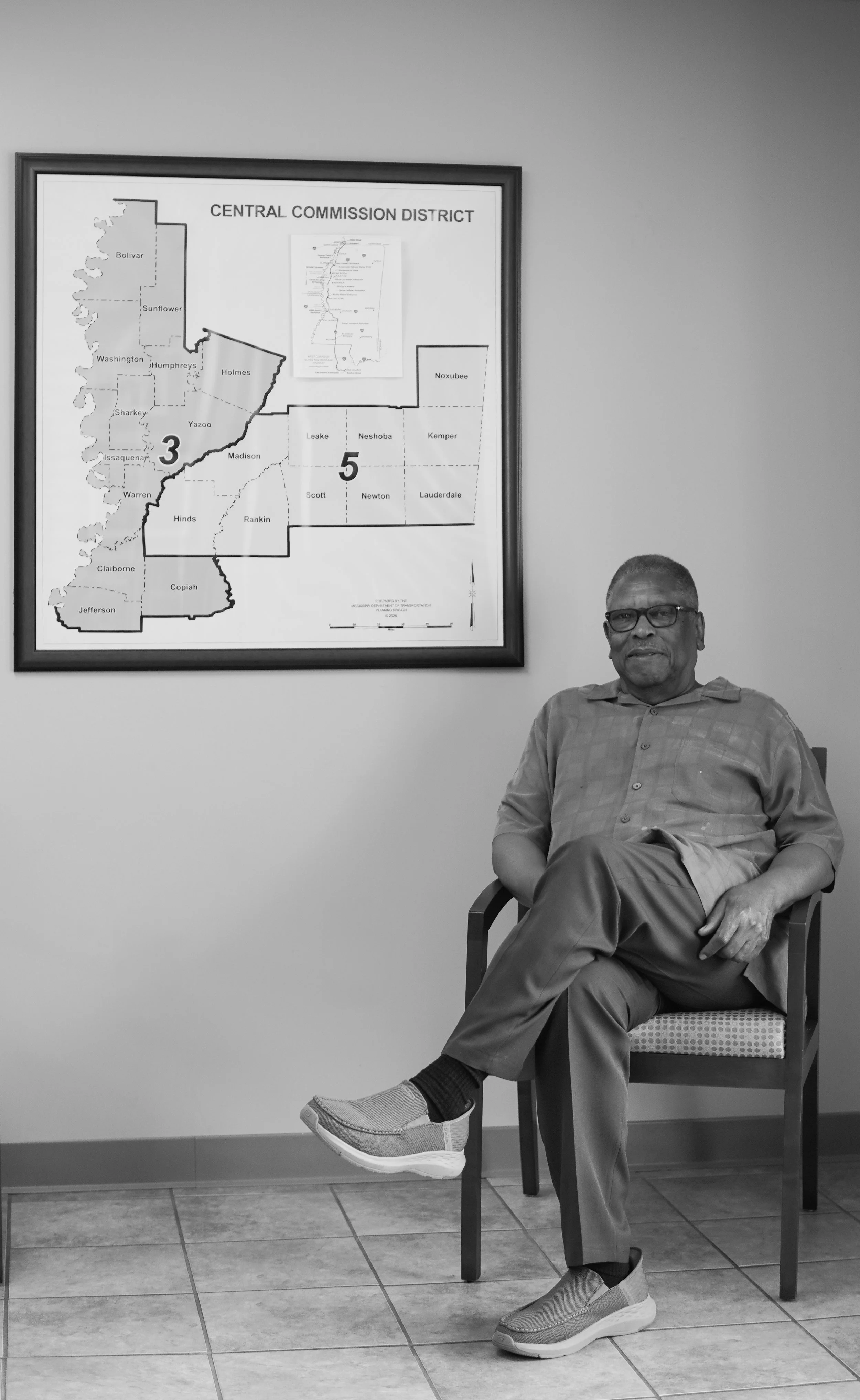

An Army veteran of the Vietnam War, Simmons served as a Mississippi State Senator for over 26 years, working across racial divisions and party lines to realize projects such as the Grammy Museum and the Terrene Landing River Park in Bolivar County. Now, he is the Central District Transportation Commissioner, representing 22 counties and approximately one million people in Mississippi.

Although Simmons now considers Cleveland, MS home, he grew up in Utica, a town to the south of the Delta. After graduating from Alcorn State University, he moved to Rosedale to teach. Moving to the Delta was “enjoyable,” but Simmons noticed differences compared to his hometown: poverty, cotton fields, educational segregation.

After serving in the U.S. Army during the Vietnam War, Simmons returned to the Delta. But little had changed. “Coming back, I saw the same thing –– the divide still existed,” he said. This observation spurred him to pursue a career in public service, so as to close social divides and eliminate the barriers preventing progress in the region.

In 1993, Simmons was elected to the Mississippi State Senate. For the next 26 years, then, he was a representative of the 13th District, which encompasses Bolivar County, Sunflower County, and Tallahatchie County. Relative to the rest of Mississippi, it is poverty-stricken.

Of the 52 State Senators, Simmons was one of 13 Black representatives, and a Democrat to boot. This placed him squarely in the minority in the State Senate. As such, he emphasized the necessity of “build[ing] bridges and cross[ing] those lines,” regardless of whether those divisions were racial or a matter of party affiliation.

According to Simmons, several of his initiatives would not have succeeded without continual collaboration with the then-lieutenant governor (now governor) of Mississippi, Tate Reeves. In Simmons’ view, relationships are “key” to political action: relationships facilitate access to resources, and resources allow for the execution of important plans.

“[Reeves is] a Republican; I’m a Democrat. He’s a white male; I’m a Black male,” Simmons said. “He’s from down south Mississippi…I’m here from the Delta. But we set aside all of those barriers, all of those lines.”

One example of Simmons’ many bipartisan efforts was the establishment of Terrene Landing in Bolivar County, which has been critical to increasing access to towns like Rosedale and bolstering tourism in Mississippi. At an event for which both Simmons and Reeves were present, Simmons presented the idea to Reeves, after which the two men worked together, ultimately acquiring the first million dollars from the state legislature to invest in Terrene.

“This year alone, over 20,000 tourists are going to get off those boats and come into the heartland of the Mississippi Delta [through Terrene],” Simmons said. “That’s a game changer.”

Likewise, Simmons also worked with Tate Reeves to obtain $6 million for the Grammy Museum in Cleveland, MS, funds that they later grew to approximately $9 million. The Museum is only the second of its kind in the U.S., and, by all accounts, rivals that of the first in Los Angeles.

Thanks to their longstanding relationship, Reeves later appointed Simmons the Chairman of the Senate Highways and Transportation Committee in the State Senate. Once again, Simmons said, this position required reaching across the aisle, obtaining the relationships and resources necessary to make change a reality.

“I don't have a Republican or Democratic or independent mile of highway or bridge in my district,” Simmons stated. “They are just highways and bridges that need resources, and I get those resources by having relationships.”

Under Simmons’ leadership, Mississippi spent over five billion dollars on improving roads, streets, and bridges, in addition to public transit, airports, railroads, and the like. He was directly involved in the repair of Highway 8 in Cleveland and the Woodrow Wilson Bridge in Jackson, as well as the construction of the Highway 82 Bypass in Leland.

By the time Simmons ran for Central District Transportation Commissioner in 2019, he had a “wealth of experience and knowledge about the system,” he said. His election was decisive, and he was re-elected for a second term in 2023.

While his role had changed, the defining challenges had not. It was always the same old story: “Trying to make everybody happy. Not having the resources to do what needs to be done.” Still, Simmons retained a strong vision for the Mississippi Delta, involving a “strategic plan” that would transform “poverty into prosperity,” shifting the region from “being dependent to being self-sufficient.”

A significant issue in the Delta is the mass exodus of its residents, including the brain drain of graduates seeking fresh opportunities beyond the region. “Jobs are not readily available [here],” Simmons lamented. “[We] don't have the bright lights of a big city like Jackson or Southhaven or Nashville, Atlanta, Dallas, Houston, New Orleans.”

The solution? To “build a taller wall”––that is, to create public infrastructure that in turn engenders more opportunities, more business, and more incentives for both locals and visitors to stay.

“I want to make sure that we create a situation where opportunities are ‘now here’ [instead of] ‘nowhere,’” Simmons said. A sign about opportunities emblazoned with the word “NOWHERE” sits in his Jackson office, inviting others to question it––and then reevaluate their own assumptions upon discovering the difference that a space makes: from “nowhere” to “now here.”

After all, the Delta is home not only to Simmons but also his family, which consists of his wife of 53 years, four children, and ten grandchildren. His daughter, Sarita Simmons, is a political leader in her own right, having successfully run for her father’s former Senate seat in 2020.

“They are folks who don't like a lot of things I do,” Simmons conceded. “But the majority of [them]…went to the polls and chose me to be their Transportation Commissioner [and] State Senator…my daughter to be a State Senator…[and] my wife to be the first Black clerk [of Bolivar County] since Reconstruction.”

What keeps Simmons going?

“Success,” said Simmons, smiling slightly. “You know, when you can plant a flower and you watch it come from the earth and grow and blossom…it makes you want to plant another one. Then…you want to plant a tree. And when you watch that tree grow, and it fruits and you can take that fruit and consume it,...you want to plant another tree…You have fruit trees, you have nut trees. You have trees that protect the environment and give you shade. You have beautiful flowers that you have planted. It motivates you to want to plant a forest.”

In a region where extensive logging and clearcutting have historically decimated tree coverage, it is poetic, perhaps, that people like Commissioner Simmons exist––that, thanks to his painstaking efforts to “plant the seeds” of growth, there are lush and enduring forests in the future of the Mississippi Delta.